Rewriting the Self: How Motherhood Redefines Identity and Well-Being

And Two Reflection Exercises

Key Ideas

The article explores the complex and evolving nature of maternal identity, highlighting how becoming a mother reshapes a woman's sense of self. Drawing on psychological theories by James Marcia and research by Konrad Piotrowski, it discusses the stages of identity development—exploration, commitment, and reconsideration—and their impact on maternal well-being.

The transition into motherhood often involves a “fracturing” of previous identities, leading to an expanded consciousness that includes the child as part of the self. This shift intensifies emotional experiences, with both heightened joy and increased vulnerability. A well-formed maternal identity is linked to better mental health, while unresolved identity crises can lead to anxiety and depression.

Reflection exercises are suggested to help readers better understand their evolving parental roles in relation to other aspects of their identities

In today's post, I would like to turn to a central theme of this Substack: maternal identity. What is a maternal identity? How does it emerge, evolve, and change over time? What are the steps to assuming a maternal identity, and what implications does this have for our functioning? What insights can understanding maternal identity offer into living, working, and playing? How does a maternal identity function alongside our other identities? We will explore these and many others throughout this Substack. For now, I would like to focus on how psychologists think about identity development and the specific domain of parental identity and then allow each of us to explore our own maternal identity through two reflection exercises.

Perhaps not surprisingly, researchers have paid relatively little attention to identity development in parents. As Konrad Piotrowski notes, “Studies on parental identity are rare.” (2018, pg. 158). However, those who have directed their efforts to understand better mothers’ internal lives offer us valuable and fascinating insights into the heart of maternal transformations. The process of coming to identify as a “mother” is rich with meaning and impact for women as they “reevaluate how their autonomy, physical appearance, sexuality, and occupations influence their identities differently than they had before motherhood” (Laney et al., 2015, p. 127).

When beginning to explore the literature on identity, one prominent theorist is James Marcia (1966), and his work on identity formation was built upon the earlier work of Erik Erickson (I’ve spoken previously about Erickson in this post). Key to Marcia’s theory is the idea of an identity “crisis” and exploration that represents a period in which one chooses between viable alternatives and then a period of commitment when one decides how much to invest in essential domains (Piotrowski, 2018). If successful, an individual gains a status of “identity achievement” that reflects the best psychological outcomes for well-being and mental health. Marcia identified four stages of identity development, with movement through them now conceived as a part of development (Meeus et al., 2010). Marcia’s stages of identity development operate along the continuums of identity exploration and commitment, resulting in four statuses: identity diffusion (low exploration, low commitment), foreclosure (low exploration, high commitment), moratorium (high exploration, low commitment), and identity achievement (high exploration, high achievement). These theoretical ideas offer us a possible base for exploring processes of maternal identity development. Still, as with much of the work that has been done on identity in the literature, Marcia’s work was primarily focused on adolescents, leaving us to wonder what, if anything, happens when a person becomes a mother.

Konrad Pietrowski has researched parental identity development and expanded on Marcia and Erickson's ideas using a more recent theoretical model by Meeus-Crocetti (Meeus, 2011). According to this model, parental identity is the level at which an individual commits to and identifies with the parental role. As one becomes a parent, an individual enters a period of identity commitment within the parenting domain. The individual develops a basic sense of confidence and commitment to the parenting role. However, this sense of identity is not static, and the mother repeatedly re-engages with her sense of parental identity, either participating in the process of in-depth exploration of the role, in which she spends a lot of time thinking about her child, seeking and gaining knowledge and strengthening her commitment, or resisting this deepening exploration. At the same time, parents also evaluate and re-evaluate their commitments to the parenting role, determining their satisfaction with having a child or reconsidering their commitment, some ultimately feeling that their choice to have a child is regretful. Such a path of reconsideration, paired with low commitment, is, not surprisingly, related to an identity crisis and poorer mental health and well-being, including high anxiety (Piotrowski, 2018), depressive symptoms (Meca et al., 2020), narcissism (Piotrowski, 2021), and perfectionism (Piotrowski, 2020). Alternatively, a well-formed parental identity, represented by a strong commitment and low reconsideration, appears protective against stress (Piotrowsiki, 2022) and is related to general life satisfaction and satisfaction with the parenting role (Piotrowski, 2022).

In a very different approach to understanding maternal identity, Laney and her colleagues at Biola University have begun to offer insights into the dramatic shifts in the psyche that happen as a person shifts from dramatic change from “I/me” to “mother.” In her qualitative work with mothers, Laney and colleagues (2015) delve into the expansion of identity around new motherhood, noting a series of processes new mothers undergo, with individual differences present at each stage. The first process they identify is “Fracturing Identities: Making space for Another.” During this early postpartum time, mothers experience a sense of self-loss and crisis as they see their old ways of being disintegrating, experiencing a fracturing of their prior identity as they work to reassemble a new identity that incorporates the child into their sense of self. As they emerge from this process, they gain a new and redefined identity, with an expanded consciousness in which the child now exists as part of themselves.

As a result of self-loss and their new sense of identity with their infant, women in the study reported being continuously aware of their children–their needs, experiences, pains, and pleasures. They reported “a kind of persistent psychological holding of the child within their awareness,” which Laney and colleagues labeled New Boundaries of the Self: An Expanded Consciousness (Laney et al., 2015, pg. 135). Lastly, the authors noted a third theme in their interviews with mothers, which they labeled the Potentiating Effects of Motherhood, in which mothers described their personalities and emotions as intensified and exaggerated. As one mother noted after the arrival of her child, “the joy is fuller, but it also increases your capacity for pain.” (Laney et al., 2015, pg. 138). Thus, motherhood introduces a crisis, redefinition, an expanded sense of consciousness, and a heightened emotional engagement in the world. These ideas speak to the enormity of what becoming a parent means to a woman’s psyche in a way that is helpful for us all to consider as we look to make meaning of how maternal identity shapes and changes us.

As I reflect upon some of the research on maternal identity, two ideas strike me. First is the idea that the research is not yet coherent in how it understands maternal identity, and perhaps this is fitting, given that the experience of becoming a mother is complex, multifaceted, and likely to be experienced in a myriad of ways by different people. Indeed, research tends to look for how people are similar rather than how they are different in its efforts to make sense of a phenomenon. But, perhaps maternal identity resists such an approach. We are each unique, and our diversity is unlikely to be captured in any one approach to understanding maternal identity.

A second idea that strikes me is that maternal identity is ever-evolving and not ever “achieved” at any one point in time. We create meaning and re-evaluate our sense of self over and over as our children grow and change, as we gain insights into ourselves, and as new challenges and accomplishments litter our path. We are not static, and neither is our sense of motherhood.

However, it is equally striking to me that our well-being is tied up in how we navigate the challenges of motherhood. In Piotrowski’s research on motherhood and Laney’s exploration of mothers’ experiences, it is apparent that how we navigate adopting a maternal identity either helps or hinders our well-being. If we come to over-identify ourselves with our children, according to Laney’s research, the boundaries between us and our children become too porous, and we lose any sense of who we are separate from the experiences of our children. This sets up a situation where we cannot separate, hindering our children’s growth and development. In Piotrowski’s research, if we ultimately decide that having children was a mistake, we find ourselves in a state of depression, anxiety, and stress. However, since identity is not static, it also seems that these negative outcomes are not written in stone. As time progresses, we can continue to grow and change and work through identity challenges with the help of insight, meaning-making, and, perhaps, a good therapist.

Two Exercises to explore your parental identity

I. Reflecting on how maternal identity fits in your set of identities

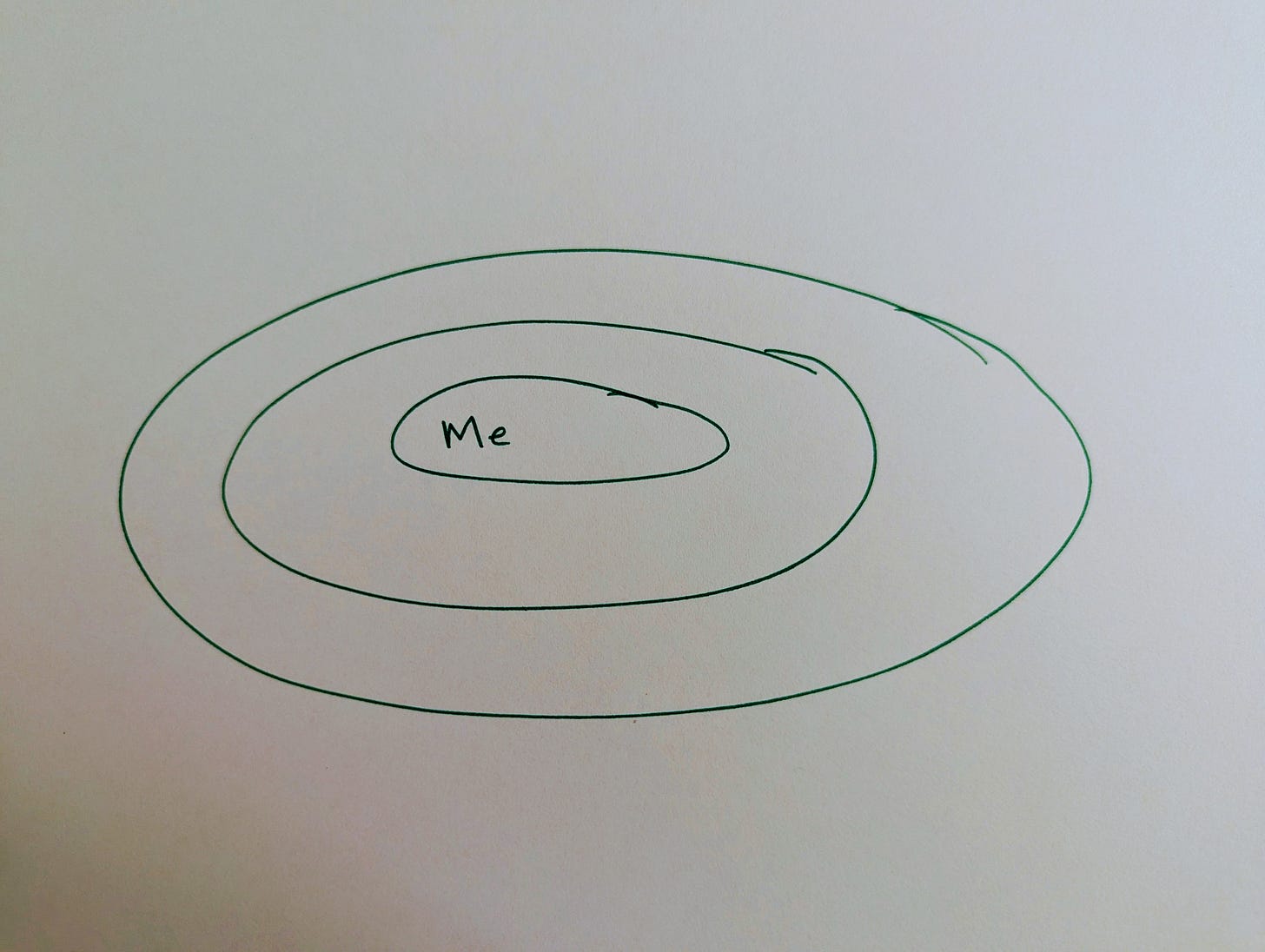

Draw a series of concentric circles or ovals on a sheet of paper. At the center, write “ME.” It may look like this:

Next, brainstorm a list of identities that you carry. You can think of differing domains such as your occupational identity, identity as a spouse or partner, sibling or friend, parental identity, or religious identity. List all that seem relevant to you, then place these identities in the circles. Aspects most central and primary to your identity go closer to the inner circle; more distal aspects are placed further out. Don’t overthink as you do this; go with what feels right.

***

Now, take a few moments to reflect on how this figure has turned out. What identity domains have you identified as very close to your core? Which are further out? Which identities were effortless to place? Which felt more difficult? Does this surprise you? What can you learn about yourself by reflecting on the salience or importance of these varying identities

II. Commitment/Exploration/Reconsideration of the Parental Role

Derived from Piotrowski’s research on parental identity, the following questionnaire (known as the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitment Scale in the Parenting Domain; Piotrowski, 2018) asks you to reflect on your parenting identity. After each statement below, mark the degree to which the statement matches your opinion.

1. Being a parent gives me security in life.

2. Being a parent gives me self-confidence.

3. Being a parent makes me feel sure of myself.

4. Being a parent gives me security for the future.

5. Being a parent allows me to face the future with optimism.

6. I try to find out a lot about my child/children.

7. I often reflect on my child/children.

8. I make a lot of effort to keep finding out new things about my child/children.

9. I often try to find out what other people think about my child/children.

10. I often talk with other people about my child/children.

11. I often think it would have been better not to have had any children.

12. I often think that not having a child/children would have made my life more interesting.

13. In fact, I believe that it would have been better for me not to have been a parent at all.

As this is a reflection exercise, it is less important to “score” your results. However, you can look at the breakdown of your totals in the following areas:

Items 1-5 center around Commitment. Commitment refers to the level of identification with the parental role.

Items 6-10 center around Exploration. Exploration refers to the extent to which individuals actively think about the commitments they have enacted, reflect on their choices, and search for additional information (Piotrowski, 2022).

Items 11-13 center around Reconsideration. Reconsideration revolves around comparing present commitments with possible alternative commitments because the current ones are no longer satisfactory.

Looking at your responses in these areas, is there anything about your parental identity that surprises you? Looking back over your time as a parent, do you think these scores have shifted or changed over time? How does the commitment, exploration, and reconsideration level help you understand yourself? How does it match up with your circle exercise from above? Remember, there are no right or wrong answers here, and questionnaires can only capture a piece of information, not the whole.

References

Laney, E. K., Hall, M. E. L., Anderson, T. L., & Willingham, M. M. (2015). Becoming a mother: The influence of motherhood on women’s identity development. Identity, 15(2), 126–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2015.1023440

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of egoidentity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Meca, A., Paulson, J. F., Webb, T. N., Kelley, M. L., & Rodil, J. C. (2020). Examination of the relationship between parenting identity and internalizing problems: a preliminary examination of gender and parental status differences. Identity 20, 92–106. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2020.1737070

Meeus, W., Van De Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S. J., & Branje, S. (2010). On the Progression and Stability of Adolescent Identity Formation: A Five-Wave Longitudinal Study in Early-to-Middle and Middle-to-Late Adolescence. Child Development, 81(5), 1565–1581. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01492.x

Meeus, W. (2011). The study of adolescent identity formation 2000–2010: A review of longitudinal research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 75–94.

Piotrowski, K. (2018). Adaptation of the Utrecht‐Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U‐ MICS ) to the measurement of the parental identity domain. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12416

Piotrowski, K. (2021). How many parents regret having children and how it is linked to their personality and health: two studies with national samples in Poland. PLoS One 16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254163

Piotrowski, K. (2022). Trajectories of parental burnout in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Family Relationships, doi: 10.1111/fare.12819